Extracted from The Testimony of Luke, by S. Kent Brown. On this section, compare Matt. 26:36–46; Mark 14:32–42.

New Rendition

39 And coming out, he went, as was his custom, to the Mount of Olives, and the disciples also followed him. 40 And when he was at the place, he said to them, “Pray that you do not enter into temptation.” 41 And he withdrew from them as far as a stone’s throw. And kneeling down he prayed, 42 saying, “Father, if you will, remove this cup from me. However, let not my will, but yours be done.” 43 And an angel from heaven was seen by him, strengthening him. 44 And being in agony he prayed more intently; and his sweat became like thick drops of blood falling down upon the ground. 45 And rising from prayer and coming to the disciples, he found them sleeping from grief. 46 And he said to them “Why do you sleep? Arise, pray that you not enter into temptation.”

Analysis

At last the Savior comes to “the hour” (22:14).[1] Throughout his ministry, he speaks openly and often to the Twelve and to others about the approach of this decisive climax (see the Notes on 9:22; 12:50; 17:25; 22:15). Now the eleven Apostles become its only witnesses,[2] perhaps aided by the memory of the unidentified young man (see Mark 14:51–52). But even the Apostles miss most of what happens because they sleep. In all, the most comprehensive account lies in the Gospel of Mark (see Mark 14:32–42).[3] Luke’s report is more spare but holds the most graphic of descriptions: Jesus’ suffering causes him to bleed through the pores of his skin. This spilling of his own blood, occurring metaphorically in the heavenly sanctuary, “the holy place,” brings about the new covenant and its associated blessing of an “eternal inheritance” (Heb. 9:12–15).

Through his divine foresight, Jesus anticipates the shocking intensity of what is coming and admits his anxiety about it all (see the Note on 12:50; also John 12:27; 18:11).[4] But by the time he climbs from Jericho to the capital city, he shows his now settled resolve to face his suffering by pushing the pace up the hill (see the Note on 19:28). However, even his divine foresight and resolve do not fully prepare him for what crashes down on him at Gethsemane—our sins on a sinless man, our wickedness on a righteous person, our guilt on an innocent soul, all of this in addition to paying the price for the transgression of Adam and Eve—“In all their afflictions [the Savior] was afflicted” (D&C 133:53; see Rom. 5:12–17; 1 Cor. 15:21–22; Alma 7:11–12).

When the moment of his suffering arrives in its fiery fury, his first reflex is to push it away; his first temptation is to escape: “Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me” (22:42). Again and again he begs his Father for a way out (see the Notes on 22:41–42).[5] As the other accounts illustrate through their verbs of repetition, he moves from standing to kneeling to standing again in an effort to diminish the awful anguish, to blunt the piercing pain (see Matt. 26:39; Mark 14:35). As his repeated visits to the Apostles (see Matt. 26:40, 43, 45; Mark 14:37, 40, 41) and as the additions to the Joseph Smith Translation illustrate (see JST Matt. 26:43; JST Mark 14:47), his suffering lasts most of the night.

But does the Savior bleed? At this point, all students of the New Testament Gospels have to make a decision: are verses 43 and 44 genuine? That is, does the angel really come and does Jesus bleed as if he is sweating? For many, these verses represent at best an independent and somewhat dubious Christian tradition that a scribe adds to a manuscript because, as theorized, Luke does not include enough about Jesus’ suffering.[6] For others, these verses are genuine.[7] For still others, these verses preserve “the most precious” of incidents from all the Gospels.[8] For Latter-day Saints, Jesus’ bleeding in Gethsemane is a fact (where else might Jesus bleed in this manner if not in Gethsemane?). It is as Luke describes and as the Risen Savior affirms: like sweat, the blood runs from “every pore” in his body. But this is not all. In the Savior’s own words, the searing “suffering caused myself, even God, the greatest of all, to tremble because of pain, and to bleed at every pore, and to suffer both body and spirit” (D&C 19:18). Not surprisingly, prophecy captures this monumental moment: “behold, blood cometh from every pore, so great shall be his anguish for the wickedness and the abominations of his people” (Mosiah 3:7). In this poignant light, we conclude that verse 44 preserves a genuine record of Jesus’ suffering.

But what about verse 43, which pictures the arrival of “an angel . . . from heaven, strengthening [ Jesus]”? The early Christian authors Justin and Irenaeus, when referring to this scene, draw attention only to the bleeding and not to the appearance of the angel. But this omission simply represents an oversight because Justin is writing about Jesus’ sufferings and Irenaeus is treating Jesus’ human nature.[9] In the case of Tatian, he includes the notice of the angel.[10] Importantly, both verse 43 and verse 44 stand together in all the manuscripts that carry them. Hence, it seems impossible to separate the two. Thus the account of the angel’s appearance is to remain with the report of Jesus’ bleeding.

For any who hold that 22:43–44 forms an insertion into Luke’s narrative and that this insertion shows Luke to be emphasizing Jesus’ prayers in contrast to his suffering,[11] we simply turn to the multitude of references where Jesus prophetically tells his closest followers that he will suffer and die (see the Note on 22:15). To be sure, if we set verses 43 and 44 aside, Mark and Matthew report much more about Jesus’ suffering, although they write nothing about answers to Jesus’ prayers except Jesus’ reference to the Father sending “more than twelve legions of angels” if only Jesus will ask (see Matt. 26:53). But when we accept these two verses as authentic, then we plainly see the underlying themes of God’s initiative in answering prayers and of Jesus’ suffering as fulfilled prophecy.

One further observation. When we think of Jesus bleeding into his clothing from “every pore,” staining thoroughly at least his inner garments, we recall the scene sketched in Isaiah 63:1–3 of the one who “cometh . . . with dyed garments . . . [and is] red in [his] apparel” and treads “the winepress alone.” This adds a significant coloration to the “coming one” of John the Baptist’s prophecy. Jesus’ coming to this moment fulfills older and deeper prophecy (see 13:35; Matt. 3:11; Mark 1:7; Acts 13:25; Mal. 3:1; Mosiah 3:9; D&C 29:11; 88:106; 133:2, 10, 17, 19, 66; the Notes on 3:16; 19:38; 20:16; 21:8, 27; the Analysis on 3:7–20 and 19:28–40).[12]

Notes

22:39 he came out: As in 21:37, Jesus exits the city. He doubtless leaves before midnight because continuing the Passover meal after midnight is forbidden and renders participants unclean.[13] When he returns, he will come back as a prisoner (see 22:54).

as he was wont: Jesus’ customary travel route takes him out of the east side of the city to the Mount of Olives rather than in another direction. Luke seems to indicate that Jesus regularly comes this way. Other reports intimate that Jesus stays in Bethany with friends (see Matt. 21:17; 26:6; Mark 11:11–12; 14:3; John 12:1), but Luke records that he spends an occasional night on the Mount of Olives (see the Note on 21:37; also John 8:1–2). Luke’s following note about “the place” hints that the mount is a regular stopping spot (22:40). On this night, Passover celebrants are not to leave the immediate environs of Jerusalem, so Jesus does not go to Bethany.[14]

to the mount of Olives: Unfortunately, Luke’s description does not assist us in locating the exact spot where Jesus and the Apostles spend the next hours. The traditional locale of Gethsemane lies on the lower slope of the Mount of Olives. But the real location of Gethsemane may be higher up the mountain.

22:40 the place: This term (Greek topos; Hebrew maqōm) often refers to a special, even sacred spot (see the Notes on 4:42; 23:33; Matt. 24:15; John 4:20).[15] Jesus’ command that his disciples pray in that spot adds weight to this view. Clearly, “the place” is the designated locale for his suffering. Only Matthew and Mark name the locale Gethsemane (Matt. 26:36; Mark 14:32). John terms it “a garden” or cultivated spot and reports that it lies on the east bank of the Kidron stream ( John 18:1). In a metaphorical sense, it becomes “the holy place” where Jesus enters to shed his blood (see Heb. 9:12–15). In a different regard, a cave near the lower, traditional location, basically a storage area for tools that gardeners use in working with olive trees, may have offered a warm nighttime resting place for Jesus and his followers because “it was cold” ( John 18:18; see the Note on 21:37).[16]

Pray: This command, when paired with the same command in 22:46, forms a bracket or inclusio for verses 40–46. The intended result for both instances is the same—to overcome temptation or trial. Jesus will now do exactly as he commands his disciples and will experience the result firsthand.[17]

temptation: The same term appears in 22:28 and 22:46. One of its meanings is “trial” (see the Notes on 4:2; 22:28, 46). The sense seems to be that disciples should avoid temptations or trials that overmatch their natural or presumed ability to overcome, because only with humility will God assist.[18]

22:41 about a stone’s cast: This notation matches others which point to a recollection of an eyewitness from whom Luke learns indirectly, or with whom Luke speaks directly (see the Note below).

kneeled down, and prayed: The report of these actions also nods toward an eyewitness account, either from one of the three Apostles who can see Jesus or, later, from Jesus himself in a later conversation with his disciples, or from the young man noted in Mark 14:51–52 (see 1:2; 6:10; 9:55; 10:23; 14:25; 19:3, 5; 22:61; 23:28; John 8:6–8; Acts 1:3–4; the Notes on 7:9, 44; 18:40; 22:31, 34).[19] The act of kneeling, also noted in Mark 14:35, “stresses the urgency and humility” of Jesus’ prayer because customarily a person stands to pray (see 18:11, 13).[20]

prayed: The Greek verb proseuchomai stands in the imperfect tense, which can mean repeated or continuous action.[21] This main verb controls the sense of the adjacent participles that are translated “kneeled down” (22:41) and “saying” (22:42). Hence, in our mind’s eye we should see Jesus kneeling, praying, and speaking the words of his prayer again and again, or over a long period of time. That is, he kneels and prays, then he kneels and prays again, and again. We compare Mark 14:35–36 (Greek text), where we also find a string of imperfect tenses in the verbs describing these acts of Jesus, all of which carry a ring of eyewitness authenticity.[22] Incidentally, Jesus and the Apostles follow later Jewish law that forbids any revelry fol- lowing the Passover meal.[23]

22:42 if thou be willing, remove: The first request out of Jesus’ mouth is that his Father take the cup away, illustrating the intensity of his agony (see the Note below). It also forms an unsuccessful attempt to shift the burden of responsibility onto his Father. It seems that Jesus requires time to gain full control of himself so that he can finally pray “nevertheless not my will.” This observation finds support in the repeating or continuous sense of the verb “prayed”—“he prayed again and again” or “he kept praying” (see Note on 22:41). It is evident that the first crushing load of pain and sin to fall on him brings him to this begging request (see Matt. 26:37–38; Mark 14:33–34).

this cup: Reference to the cup, which Jesus shares with his disciples a short while before, occurs in each of the Synoptic accounts of Jesus’ prayer (see Matt. 26:39; Mark 14:36; also 3 Ne. 11:11). The tie to the two cups poured by Jesus at the supper is not to be missed (see 22:17–18, 20). Thus Jesus’ Atonement links closely with sacred ceremony, sacred actions. The first of the cups nods toward the messianic banquet at the end of time; the second points directly to Jesus’ atoning blood. In this latter instance, the mention of the cup may possibly tie to the general concept of “the cup of the wine of the fierceness of [God’s] wrath” (Rev. 16:19; also Rev. 14:10; 3 Ne. 11:11; D&C 103:3). Notably, scripture paints divine wrath either as a liquid (see Job 21:20; Jer. 25:15–16; Hosea 5:10; Rev. 14:10; 19:15; Mosiah 5:5) or as a fire kindled by him (see Num. 11:33; Ps. 106:40; Jer. 44:6).[24]186 John 18:11 rehearses Jesus’ words to Peter about “the cup” at the time of his arrest, a reference that captures the meaning of this expression—“the cup which my Father hath given me, shall I not drink it?” Not incidentally, Luke alone records Jesus sharing two cups at the supper (see 22:17, 20). The other accounts mention only one, that which points to Jesus’ atoning blood. What are we to make of Luke’s double reference to the cup? Both of them point to the future, one immediate (the Atonement) and one far away (the messianic banquet). But they both form a ceremonial tie to Jesus’ work as conqueror of the difficulties of this world.

not my will: Finally, after praying and supplicating “with strong crying and tears” (Heb. 5:7), Jesus surmounts the temptation to back out of his suffering and submits to his Father’s will.

22:43 And there appeared: This verse and the next are not part of the earliest manuscript (75) or other important manuscripts of Luke’s Gospel. Hence, many scholars doubt their authenticity.[25] A few manuscripts place these verses after Matthew 26:39. Recent studies on P 69, a fragmentary text from the third century (held at Oxford) that preserves only a few verses from Luke 22 and omits verses 41–44 instead of just verses 43–44, illustrate that some early texts of these verses are in flux and unsettled.[26] Early Christian authors who quote passages from the Gospels—for example, the second-century writers Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and likely Tatian—show an acquaintance with the scenes painted in 22:43–44, specifically Jesus’ bleeding.[27] Other textual evidence points to their genuine character.[28] In another vein, the verb translated “there appeared” (Greek horaō) actually stands in the passive voice: literally “the angel was seen” by Jesus, underscoring not only the divine initiative to assist him[29] but especially Jesus’ direct sight of this celestial personality, a prominent theme in Luke (see the Notes on 1:11, 12, 29; 24:24, 31, 34).[30] On the question whether Jesus generally needs assistance from angels, see the Note on 4:13.

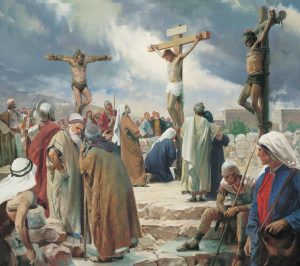

an angel: The angel’s appearance is a favorite image among painters of religious art. The identity of the angel remains unknown. But the angel’s coming demonstrates the truth of Jesus’ instruction to the Apostles, that prayer will bring results, including heavenly assistance in trials (see 22:40, 46).[31]

22:44 And being: The content of this verse is certainly accurate because Jesus’ bleeding is confirmed both in prophecy (see Mosiah 3:7) and in the Risen Savior’s personal reminiscence of his experience (see D&C 19:18).

being in an agony: Perhaps oddly, before this point Luke offers few clues to us that Jesus is in deep agony, except the imperfect verb “prayed” that nods toward repeated or continuous praying (see the Note on 22:41). This differs from the other accounts wherein Jesus verbalizes his sudden anguish (see Matt. 26:37–38; Mark 14:33–34). Some scholars who believe that verses 43–44 are added by later scribes also judge that, in Luke’s portrayal, Jesus does not suffer deep distress about the troubles that are about to engulf him. Rather, he faces them in a way that becomes an example to later believers.[32]

prayed more earnestly: Without speaking directly about the intensity of Jesus’ suffering, this note discloses that he is pleading desperately for help. As in 22:41, the verb is in the imperfect mood and points to repeated and continual praying (see the Note on 22:41).

his sweat: Luke graphically pictures that all of Jesus’ body is affected by his suffering, as if he is working hard, like an athlete, and his entire body is sweating, from his head to his feet: “profuse sweat.”[33] The Joseph Smith Translation renders the expression differently, changing the noun to a verb: “he sweat” (JST 22:44).

as it were: The force of the Greek comparative particle hōsei is difficult to judge. Some scholars propose that it means “like” and thus they translate “his sweat became like drops of blood” or “the sweat was falling like drops of blood,” thus discounting that Jesus actually sheds blood in Gethsemane.[34] The other sense for hōsei is “as” (see 24:11; Matt. 28:4; Mark 9:26; Rom. 6:13), that is, “his sweat came to be as drops of blood.”[35]

drops of blood: The term translated “drops” (Greek thrombos) appears only here in the entire New Testament. The word can mean “clot” or “small amount of blood.”[36]

falling down to the ground: The blood that oozes from Jesus’ skin does not simply cover and discolor his body but comes in such amounts that the fluid gathers on and drops from the skin of his face. This circumstance raises questions about how art portrays Jesus both in Gethsemane and after- ward, until his execution—he freely bleeds at least into his underclothes, staining them, as the expression “every pore” strongly hints (Mosiah 3:7; D&C 19:18).

22:45 when he rose up: The verb “found” governs this participle and is the simple past tense in Greek, thus conveying to the reader the sense that Jesus prays a long time and then stands up. Incidentally, the verb “to rise up” (Greek anistēmi) describes the resurrection in a few passages (see 9:8, 19; 16:31; 18:33; 24:7, 46).[37] Mark’s report pictures the scene very differently, that Jesus goes forward and falls and prays, then goes forward and falls and prays, actions underscored by the repetitive force of the imperfect verbs (see Mark 14:35). Luke’s adoption of the imperfect verb “he prayed” fits into this view of events (22:41, 44; see the Note on 22:41). In this connection, both Matthew and Mark report that Jesus walks three times to check on Peter, James, and John during this extended experience (see Matt. 26:40, 43, 45; Mark 14:37, 40, 41). Luke reports only one such contact. Luke seems to be placing more emphasis on Jesus’ act of praying and less on his interaction with the Apostles.[38]

for sorrow: The prepositional phrase means “from sorrow” (Greek apo tēs lypēs). The New English Bible renders the phrase “worn out by grief.” That sorrow or grief characterize the past days and hours which the Apostles, particularly Peter, spend with Jesus is certainly a matter of record: “being aggrieved” ( JST 22:33; also John 14:1, 27). The Joseph Smith Translation adjusts “for sorrow” to “for they were filled with sorrow” ( JST 22:45).

22:46 Why sleep ye?: The synoptic Gospels document the Apostles’ fatigue (see Matt. 26:40, 43, 45; Mark 14:37, 40, 41). But only the Joseph Smith Translation hints at the length of their sleep: Judas and the arresting party approach “after they had finished their sleep” ( JST Mark 14:47; also JST Matt. 26:43). This added note indicates that they sleep about as much as they customarily do, that is, much of the night, and that the early dawn draws near (see the Note on 22:60). In this light, and in agreement with Jesus’ repeated returns to the slumbering Apostles, Jesus’ suffering in Gethsemane lasts a large portion of the night.

rise: The Greek verb anistēmi, which here is a participle, can bear the sense “to rise again,” that is, to resurrect.[39] Hence, Jesus’ words to the three Apostles may form a mild hint at his own future resurrection (see the Note on 22:45).

pray: This instruction to pray illustrates an important principle. The divine world seems to be persuaded, perhaps even supported, by the prayer of the righteous (see Jer. 7:16; James 5:16; the Note on 10:2). Such appears to be the case when Jesus instructs followers in the New World to pray even while he is in their midst (see 3 Ne. 19:17–18, 22–26, 30; 20:1).

lest ye enter into temptation: The expression here is stronger than that in 22:40. Is it possible that Jesus’ experience in Gethsemane brings him to express himself more forcefully? That certainly seems to be the case in Mark 14:38, where Jesus’ words brim with meaning because he faces the temptation not to go through with the Atonement—“The spirit truly is ready, but the flesh is weak.”[40]

temptation: The sense may reflect both meanings of this term: (1) to be tempted to do or think something inappropriate, or (2) to undergo a trial of some sort (see the Notes on 4:2; 22:28, 40). The appearance of the word “temptation” means that an overtone of Jesus’ prior temptations at the hands of the devil also lingers here (see 4:2–13). In that earlier case, the devil himself administers the temptations. None of his minions take the lead. We can be certain that Satan comes to Jerusalem both to influence Judas (see the Notes on 22:3, 31) and for Jesus’ last hours (see 22:53—“this is your hour, and the power of darkness”). Hence, Satan’s presence may be one of the reasons for Jesus’ instruction that his three chief Apostles pray.

[1] S. Kent Brown, “Gethsemane,” in EM, 2:542–43.

[2] Branscomb, Gospel of Mark, 267.

[3] Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 197–201.

[4] Barrett, Gospel according to St John, 436; Marshall, Luke, 547; Morris, Luke, 340– 41; Clivaz, L’Ange et la Sueur de Sang, 411–51, 626–33.

[5] Maxwell, “New Testament,” 26–27.

[6] Fitzmyer, Luke, 2:1443–45; Stein, Luke, 559; Ehrman, New Testament: A Histori- cal Introduction, 124.

[7] Marshall, Luke, 832, “with very considerable hesitation”; Brown, Death, 1:185; Morris, Luke, 340.

[8] Plummer, Luke, 509, quoting B. F. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort, early scholars of the New Testament text.

[9] Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 103.8; Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses 3.22.2.

[10] Tatian, Diatessaron 48:16–17.

[11] Ehrman, New Testament: A Historical Introduction, 124.

[12] TDNT, 2:666–69.

[13] Mishnah Pesahim 10:9.

[14] Jeremias, Eucharistic Words, 55.

[15] TDNT, 8:195–99, 203–5; TDOT, 8:537–43.

[16] Wilkinson, Jerusalem as Jesus Knew It, 130–31; Taylor, “Garden of Gethsemane,” 26–35, 62.

[17] Green, Luke, 777.

[18] TDNT, 6:28–29.

[19] Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, 200–201.

[20] Marshall, Luke, 830.

[21] Smyth, Greek Grammar, §§1790, 1890–94, 2341; Blass and Debrunner, Greek Grammar, §325, 327.

[22] Branscomb, Gospel of Mark, 267.

[23] Mishnah Pesahim 10:8.

[24] Charles, Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John, 2:14–17.

[25] For example, Bart D. Ehrman and Mark A. Plunkett, “The Angel and the Agony: The Textual Problem of Luke 22:43–44,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 45, no. 3 (1983): 401– 16; Fitzmyer, Luke, 2:1443–45; Stein, Luke, 559; Ehrman, New Testament: A Historical Introduction, 124.

[26] Thomas A. Wayment, “A New Transcription of P. Oxy. 2383 (P69),” Novum Testamentum 50, no. 4 (2008): 351–57; see also Claire Clivaz, L’Ange et la Sueur de Sang: Ou comment on pourrait bien encore écrire l’histoire, vol. 7 of Biblical Tools and Studies (Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2010), 460–65, 627.

[27] Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 103.8; Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses 3.22.2; Tatian, Diatessaron 48.17.

[28] Bovon, Luke 3, 197–99; Lincoln H. Blumell, “Luke 22:43–44: An Anti-Docetic Interpolation or an Apologetic Omission?” TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism 19 (2014): 1–35; see also Clivaz, L’Ange et la Sueur de Sang, 609–18, 633–39.

[29] BAGD, 581–82; Brown, Death, 1:186.

[30] TDNT, 5:317, 324, 342.

[31] Fitzmyer, Luke, 2:1444.

[32] For example, Stein, Luke, 559; Ehrman, New Testament: A Historical Introduction, 124.

[33] Johnson, Luke, 355; Tannehill, Luke, 324.

[34] Marshall, Luke, 832–33; Fitzmyer, Luke, 2:1444–45; Bock, Luke, 2:1761–62.

[35] Plummer, Luke, 510–11; Liddell and Scott, Greek Lexicon, 2040; Blass and Debrunner, Greek Grammar, §453(3); BAGD, 907.

[36] Liddell and Scott, Lexicon, 807; BAGD, 364.

[37] BAGD, 69; TDNT, 1:369–71.

[38] Marshall, Luke, 833.

[39] BAGD, 69; TDNT, 1:369–71.

[40] Neal A. Maxwell, “The New Testament—a Matchless Portrait of the Savior,” Ensign 16 (December 1986): 20–27.