This text is excerpted from The Parables of Jesus: Revealing the Plan of Salvation, by John W. Welch and Jeannie S. Welch, with art by Jorge Cocco Santangelo and art commentary by Herman du Toit. The book is available from Amazon here. Used by permission.

Following directly after the parable of the sower comes the parable of the wheat and tares. It adds one more cruelty to the list of things that the sower’s enemy will perpetrate in trying to diminish or destroy the efforts of the sower.

Jesus can be found quite clearly in this parable as the master of the household (see Matthew 13:27), the one who planted the field with good seed. The enemy who comes as men sleep and who then sows the field with the seed of a certain kind of weed called zizania is identified and referred to in the parable of the sower as the evil one, Satan, or the devil.

Jesus’s surprising but highly sensible solution to this problem is to allow the wheat and the tares to grow together.

SETTING AND CONTEXT

This parable is found only in what is sometimes called the “parable sermon” in Matthew 13 and is the second in that series of kingdom parables. As such it can be most specifically understood as a sequel to the parable of the sower. In the context of the historical playing out of the plan of salvation, the parable of the wheat and tares makes it prophetically clear that problems will arise shortly after the sower plants the field.

Perhaps a question had arisen about impending problems, because the parable of the sower said nothing about the evil one ever going away. Instead, he is persistently present, trying to snatch away the word from the hearts of people, causing tribulation, persecution, and temptation. Individual offenses will occur, but “On how wide a scale?” A logical second question would have been, “When might these serious, field-wide problems arise?”

The parable of the wheat and tares implies that troubles would arise soon after Jesus had started His Church and that they would be widespread throughout it. As soon as the householder was gone and while his workers “slept,” the enemy would sow the field with the seeds of weeds that look like wheat but are not. These look-alikes could be anti-Christs (literally look-alikes), false prophets, false doctrines, or competing alternates for the gospel. This parable thus gives a foreboding prophecy of coming problems, some of which were probably already beginning to be felt by the disciples, in addition to other difficulties that would soon actually be faced in early Christianity, eventually leading to a great apostasy. Being hard to detect, the “children of the wicked one” came soon as wolves disguised in sheep’s clothing (see Matthew 7:15; Acts 20:29). Their false doctrines were sometimes hard to distinguish from Christ’s true teachings, and just as wheat and zizania look a lot alike in the field—at least until they produce their final heads of either heavy wheat kernels or weightless weed seed[1]—so these teachings and practices would be hard to distinguish initially from the true doctrines.

Wisely, the master of the household counseled his zealous workers to allow the wheat and the tares to grow together until the time of the harvest. Just as “it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things” (2 Nephi 2:11), it is necessary to recognize this fundamental state of elemental opposition that exists in this world, something that is necessary to test the mortal soul in his life journey. Workers in the kingdom of heaven must be patient and watchful, for pulling the tares up too soon would root up the wheat at the same time.

Although it will be difficult for people to tell the difference between good wheat and false tares, at harvest time those distinctions will become apparent. In the end, the righteous will be harvested and gathered in, while the tares will be burned as stubble.

TEXT AND COMMENTARY

Another parable put he forth unto them, saying, The kingdom of heaven is likened unto a man which sowed good seed in his field: But while men [his workers] slept, his enemy came and sowed tares [zizania weeds] among the wheat, and went his way [slipped away]. But when the blade was sprung up, and brought forth fruit [formed heads], then appeared the tares also. So the servants of the householder came and said unto him, Sir, didst not thou sow good seed in thy field? from whence then hath it tares? He said unto them, An enemy hath done this. The servants said unto him, Wilt thou then that we go and gather them up? But he said, Nay; lest while ye gather up the tares, ye root up also the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest: and in the time of harvest I will say to the reapers, Gather ye together first the tares, and bind them in bundles to burn them: but gather the wheat into my barn. (Matthew 13:24–30)

Then Jesus sent the multitude away, and went into the house: and his disciples came unto him, saying, Declare [explain] unto us the parable of the tares of the field. He answered and said unto them, He that soweth the good seed is the Son of man; The field is the world; the good seed are the children of the kingdom; but the tares are the children of the wicked one; The enemy that sowed them is the devil; the harvest is the end of the world; and the reapers are the angels [messengers]. As therefore the tares are gathered and burned in the fire; so shall it be in the end of this world. The Son of man shall send forth his angels [messengers], and they shall gather out of his kingdom all things that offend, and them which do iniquity; And shall cast them into a furnace of fire: there shall be wailing and gnashing of teeth. Then shall the righteous shine forth as the sun in the kingdom of their Father. Who hath ears to hear, let him hear. (Matthew 13:36–41)

This parable first addresses the challenges presented by apostasy in the early Christian church, its communities, and its families. It then turns attention to the final states of the evil and of the righteous at the end of the world. The conclusion of this parable will be discussed in Chapter 18 (pp. 148–150). But at this point we turn attention to the inevitable development of apostasy following Jesus’s planting of the seeds of the kingdom during His mortal ministry. As this parable of the wheat and tares makes clear, all of this was anticipated by the Lord, including the solution of encouraging Church members to recognize the alternative for what it is and to coexist distinctively with opposition as called to do under the plan of salvation.

To understand all of this, it is helpful to compare the words of this parable with what is taught in the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants about the realities of apostasy, restoration, and final judgment in the chronological unfolding of the plan of salvation.

In the Book of Mormon, three steps toward the Apostasy following the ministry of Christ were foreseen in vision long ago by Nephi:

Step 1: After the gospel of Jesus Christ had been preached, the plan contemplated that things would be taken away, not at first from the texts of the Bible, but from the gospel itself. In the words of the angel, people would take “away from the gospel of the Lamb many parts which are plain and most precious” (1 Nephi 13:26; emphasis added). This could have occurred simply by altering the meaning or understanding of the concepts taught by the Lord. For example, when people lost the part of the gospel that understands faith as faithfulness as demonstrated by good works (as is stated most clearly in the early New Testament Epistle of James), people lost something very important about the essential nature of true faith, obedience, power, and loyalty, and not just as a confessional or mental state. Or when they lost an understanding of the precious covenantal bonds of eternal marriage as God had intended at the beginning when He “joined together” the man and the woman (Matthew 19:4–6), people lost the plain rationale with which they could have later resisted the rise of celibacy in the generations after the deaths of the Apostles.

Step 2: The angel said to Nephi that people would take away “many covenants of the Lord” (1 Nephi 13:26). For example, neglecting, changing, and then eliminating the covenantal aspect of baptism when they moved from adult baptism to infant baptism, they removed from the baptismal ordinance its previously understood role as an outward sign of adult repentance and an inward covenantal submission to membership in the fold of God.[2]

Their diminishing of the role of covenant renewal as a part of partaking of the sacrament each week might be a related consequence of the loss of the idea of the baptismal covenant as well. Evidences of temple covenants amidst early Christian writings and practices have also been identified by scholars,[3] but those temple covenants and ordinances also fell by the wayside. Nephi’s text indicates that some people would even intentionally change the covenants or take them away so “that they might pervert the right ways of the Lord, that they might blind the eyes and harden the hearts of the children of men” (1 Nephi 13:27).

Step 3: Finally, Nephi beheld that “many plain and precious things [were] taken away from the book” (1 Nephi 13:28; emphasis added). This could have occurred either by the physical loss of words or as a consequence of still-existing texts no longer being understood, being supplanted or overshadowed by look-alike alternates.

But the foreordained plan of mercy provided ways in which additional records would come forth to establish the truth of the first” and to “make known the plain and precious things which have been taken away from them.” Above all, these records would establish “that the Lamb of God is the Son of the Eternal Father, and the Savior of the world; and that all men must come unto him, or they cannot be saved” (1 Nephi 13:40).

Two sections in the Doctrine and Covenants also speak about the causes of these early apostate problems. Sometimes the cause was internal, as conflicts arose. Speaking to his young priesthood leaders in Ohio in 1831, the Lord said: “My disciples, in days of old, sought occasion against one another and forgave not one another in their hearts; and for this evil they were afflicted and sorely chastened” (D&C 64:8). Although brief, this statement uncovers a profound insight: some troubles that plagued the early Christian church were caused by internal disharmony and aggressive confrontations among the leaders of the early church. We do not know how these problems began, or who first took offense. But the solution should have been to coexist and work through those proposed reforms or innovations. Instead, their failure to forgive one another made them look like the eager farmhand who wanted to quickly and angrily cut out the tares from among the wheat. In doing so, this unwisely did more damage than could be tolerated. The preemptive cure turned out to be worse than the disease.

Second, in Doctrine and Covenants 86, revealed in 1832, the Lord Himself provides an authoritative retelling and reapplication of the parable of the wheat and tares to the last days leading up to the final harvest. This modern interpretation applies the parable to the last dispensation—to its gatherings, harvests, and the coming day of judgment. But this elaboration of the parable also clarifies a few details about the early situation after the resurrection and ascension of Jesus. It tells us that the tares were sown in the field not only when the workers slept, but also afterwards as well, and as a result Satan sits in the hearts of men (see D&C 86:3). Moreover, it says that at least some of the wheat would be choked out by the tares, so much so that the early Church was actually driven out into the wilderness (see D&C 86:3), which occurred at a time when the blade was yet tender (see D&C 86:4).

Eventually, however, the heavier heads of wheat will bend over, while the light and empty heads of the tares remain standing straight up. This contrast would seem to compare the haughty pride of the children of evil with the humble bowing down of the righteous. In addition, even though the Church proper had fled, it is clear that much wheat remained in the field along with the tares. That will be the valuable harvest that angelic messengers[4] are already crying and waiting to be sent forth to commence gathering (see D&C 86:5). In the end, Section 86 makes it clear that only through the rights, revealed guidance, and spiritual lineage of the enduring priesthood (see D&C 86:8) can one succeed in “the gathering of the wheat” (see D&C 86:7). If they continue in the Lord’s goodness, the lawful heirs of that priesthood will be “a light” unto the world that can accurately and authoritatively distinguish between what is wheat and what is tare, and through that be “a savior” (D&C 86:11) unto all of God’s children.

[Commentary on this parable continues in another section of the book, pages 148-151, and focuses on the parable’s revealing God’s judgment as separation and purging.]

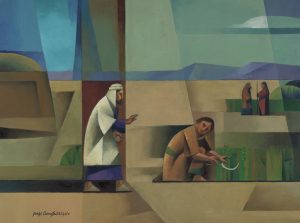

LET THEM BOTH GROW TOGETHER [art commentary by Herman du Toit]

The main figure in this painting is the householder, who represents the Lord. He is seen cautioning, warning, and advising his servant. The worker is about to cut into the tares and also the wheat with his sickle. The householder gestures toward the farmhand with his right hand to stop the worker from damaging the wheat. In so doing the householder’s hand transgresses the vertical division that separates his spiritual realm from the temporal world of the worker. This act of gentle communication symbolically represents revelation.

The householder’s white and purple clothes give an impression of his royalty and even high-priestly attributes. He is a man of substance, and his substantial home, on the left of the composition, is built to last. His heavenly wisdom is suggested in the brightest blue plane that beams down upon him and his house from above.

The farmhand, looking back at the householder, is impatiently ready to cut and eliminate the tares. His shortsighted temporal view is suggested by the earth tones of the parallelograms above and below him. But the householder prevails in time to give instructions to let the wheat and tares grow and coexist together for the season.

Two workers out in the field on the upper right patiently watch while the wheat ripens. They are not working, but standing by, waiting for the harvest season to arrive. The cloud above may symbolize the heavenly rains that will, in the meantime, fall on both the righteous and the wicked.

The earth tones in the foreground are appropriate for the field in which the wheat and zizania seeds were initially planted. Moving off into the distance, heaven and earth are separated by a clear horizon. The purple hills may stand for the sacred wilderness into which some of the wheat has fled and taken refuge. Those heights may now also invite viewers to come up into the mountain of the Lord and to look ahead to the glorious harvest of light and goodness that lies in the future for those who will, in the end, shine as the sun in the Father’s kingdom.

[1] Examination of this parable as the scriptural paradigm for detecting, understanding, and correcting the Apostasy is found in John W. Welch, “Modern Revelation: A Guide to Research about the Apostasy,” in Early Christians in Disarray: Contemporary LDS Perspectives on the Christian Apostasy, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 2005), 101–132.

[2] The covenantal or contractual meaning of the word answer in 1 Peter 3:21 may reflect this early understanding, which is also taught throughout the Book of Mormon. See Noel B. Reynolds, “Understanding Christian Baptism through the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 51, no. 2 (2012): 4–37.

[3] See, for example, Hugh W. Nibley, Mormonism and Early Christianity, volume 4 of The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1987). See also Welch, Illuminating the Sermon at the Temple, 47–114.

[4] 4. Jesus called God’s reapers “his angels” (Matthew 13:41), and the Joseph Smith Translation identified them as “the messengers sent from heaven” (Matthew 13:40 JST), a possible reference to angelic messengers, such as Moroni and John the Baptist, who were sent by the Son of man to commence the gathering of the righteous throughout the earth. The Greek word for angels is aggelous (pronounced angelous), which is the normal Greek word for both angels and messengers.